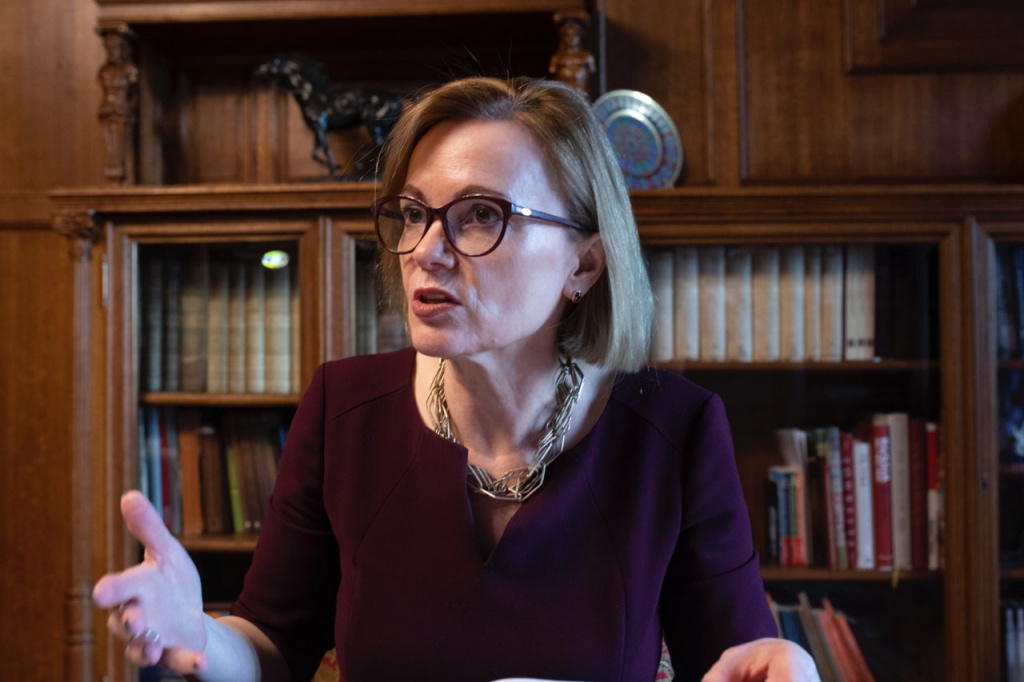

British Ambassador to Russia Deborah Bronnert: We are ready to work with Russia to solve global challenges

Deborah Bronnert

Photo: Press Office of the British Embassy in Russia

British Ambassador to Russia Deborah Bronnert has given an interview to Interfax in which she speaks about bilateral relations with Russia, cooperation on climate change and biodiversity loss, and fight against the pandemic and comments on London's position on nuclear deterrence and the Treaty on Open Skies.

Question: Russia was named the main threat in the UK's Integrated Review of Security, Defense, Development and Foreign Policy. Does it mean that the UK is now blacklisting Moscow and actually giving up on developing bilateral relations and what is exactly the threat that UK sees from Russia?

Answer: Thank you for the question. If I may, I want to start by talking in general terms about what the Review is, and then I'll answer your specific question.

So, what is the Integrated Review and what are we trying to achieve? Well, as you said, it's about the United Kingdom and how we set our global strategic and forward-looking vision for the UK on defense diplomacy and international development to 2030. I have to say it's not an 'обзор.' It's first and foremost about the UK's place in the world and how we see that evolving over the rest of this decade. The UK public - and my prime minister said that very clearly in parliament - expect us to make our country stronger, safer and more prosperous. And the Integrated Review sets out how we want to achieve that as a positive influencer in the world, as a vital part of the Euro-Atlantic community, a member of NATO, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, this year we of course are chairing the G7, we are also co-hosting with Italy the United Nations climate talks, COP26, and we are also the G7 largest contributor of humanitarian assistance to developing countries. And this is the first such strategy that we published since we fully left the European Union, so of course you would expect a very strong emphasis on sovereignty, on self-determination, but it is a positive outward-looking agenda. As part of that of course we are also clear within this about threats and challenges that we're facing. Actually, we identify dangerous climate change and biodiversity loss as our biggest global challenge, and that's an issue on which we want to work with all countries, including Russia, in order to find solutions that will safeguard the future of our planet, which is our common home.

Systemic competition between liberal and democratic states and those with an authoritarian approach is real. We identify China and China's more assertive stance as one that requires a response. And you are absolutely correct, we have identified in terms of state-based threats, we've identified the most acute threat to the UK, to European security is Russia. That's for a series of reasons, I think they are pretty well known. My prime minister referred to the attack in Salisbury in 2018 in Parliament. It's clear this is not the relationship that we want with Russia, but we can't return to a normal relationship with Russia, unless Russia changes its approach, unless Russia stops taking these threatening actions against the UK and our allies. Clearly, from the UK, from the embassy perspective, this doesn't mean that we don't want to talk to Russia. Certainly, I've mentioned climate – and I'm sure we'll talk about that in more detail – but we are talking to Russia about a range of global challenges, and of course my embassy and others are continuing to build strong ties between British and Russian people, institutions and businesses to promote and encourage cooperation whether that's science, education, culture, arts and sanctions compliant trade. I think I've set out in terms of answering your question what we are trying to do with - I shouldn't call it review, it doesn't work – the strategy because I think that translates better. It is obviously in its analysis looking at our experience, the world looking at our experience of Russia's state behavior, and that's how we've come to the judgements we've come to. We are looking forward and we are seeking to describe how we think the UK, the UK government can help deliver a safer and a better world. I don't think it should be surprise that we have named Russia in terms of our country-based as the most acute threat to our security; it's based on Russian behaviors and actions. What we seek is not what we have sought, but we have to talk about the world as we find it and we have to deal with the world as we find it.

Q.: Russian Ambassador in London Andrei Kelin has recently said that political relations between Russia and the UK are "practically dead". Do you agree with his opinion? In what areas primarily are difficulties now expected to arise?

A.: So, I have huge respect to my counterpart in London. I would say that despite the really challenging political circumstances and relationship, we do keep channels of communication open. We are and will continue to work with Russia to address international issues of peace and security, particularly of course as those that are in the realm of permanent members of the Security Council, and that means that we continuing to work with Russia to address such issues as the Iranian nuclear program and on areas where we have different perspectives, and that for example would include Syria. I've already said that our biggest international priority is addressing the risks of climate change and biodiversity loss. I think there is a lot to do on that agenda, we are doing a lot. That's an area on which we are working with Russia and will continue to work with Russia both at the political level - because it is an intentionally political question – but also on many other levels. For example, one of the core themes of the Integrated Review is the importance of science and technology and the fantastic science base that we have in the UK. Today, we have Carole Mundell, who is our chief international science envoy, she began a virtual visit to Russia a few days ago. She had a discussion with the Russian Academy of Sciences and other government officials. She did further engagements on Wednesday, and she was talking about scientific collaboration between the UK and Russia. The discussions I was involved in a few days ago were really focused on health issues, Covid, and climate, and also astrophysics – she is a professor of astrophysics. So, we are continuing – and I mean this is a very concrete example about how we are continuing to have that kind of engagements.

Last week we marked the 100 years of the establishment of the – I guess it would be - the Soviet trade delegation that has become the Russian trade delegation in London. One of the things we were talking about is trade and investment between the UK and Russia - I think you are going to ask me about that later. So, there are a lot of practical examples of us continuing to engage and work together. But that is not to detract from the very serious problems, if they are as well. Of course I should also say that people-to-people work is continuing. It's tougher at the moment because of Covid of course, but I think we are hopeful that in the course of this year we can again pick up some of the things that we just couldn't do last year because of the pandemic, and that's on culture, on education, on arts, as well as on trade. I think that's probably a pretty comprehensive answer to the question, but, as I said, I'm not trying to downplay the difficulties, but the relationship is broader than those areas of very significant disagreement that we have.

Q.: But let’s give some hope to our readers: are there any spheres for cooperation between Russia and the UK? Maybe our policies on climate change may become a touch point?

A.: We've identified dangerous climate changes and biodiversity loss as a huge global challenge that all countries need to come together and tackle collectively. I think it is very positive that Russian joined the Paris Agreement back in autumn 2019 now, and that means that Russia is participating in the preparations and will be a part of COP26, which, as I've said, will take place in Glasgow in November this year – it was due to be last year but was suspended due to the pandemic. What we are doing and others are doing is encouraging all parties to be more ambitious, to work together to reduce carbon emissions, so that we can avoid dangerous climate change. The UN has been very clear that we are not there yet, we need more action from everyone, but in particular we need more action from the big polluters, and Russia, I think, is the fourth major global carbon emitter. We need Russia to be more ambitious. The UK, Japan, [South] Korea, the European Union, the U.S., China have now all publically committed themselves to the net zero target. The majority of those for 2050, I think, China is 2060. Obviously, what we would like is Russia to also commit itself to the net zero target and come forward with detailed plans about how Russia would reach that. We are also very conscious that Russia is home to a fantastic range of biodiversity and to a very significant proportion of the world's forests – over 20% of the world's forests. That of course means that Russia has a great potential. Forests, as you know, play a huge role as carbon sinks. The way those forests are managed can increase that and make even a bigger contribution. We are certainly talking to the Russian government, Russian science, Russian business about ways we can work together on forestry in order to help maximize that potential. I should say within all of this we are very conscious that countries want to grow their economies, while also guarding against dangerous climate change, and certainly again the experience of the UK that we can do that, we have done that, we are determined that we become more prosperous, while following a sustainable development path. So, we are talking to Russia about what we've done and looking at this sort of issues where we know that Russia has identified they may have advantages in terms of low carbon grade, so hydrogen as energy source is one example of that.

In terms of the conversation that we have at the political level, clearly there are conversations going on in the UN framework, but when our FCDO Minister Wendy Morton visited last November, one of the themes of her visit was about climate change and preparation for COP26. One of our environment ministers, Lord Goldsmith, had a virtual meeting with the president's climate advisor Ruslan Edelgeriyev – I think it was end of February. They talked about possible areas of cooperation, I've mentioned forest management and we also with a lot interest at the Sakhalin low carbon pilot project to see whether that provides goal for cooperation, too. I should mention that I was in the Lake Baikal, two weeks ago, together with the UN Environmental Program Goodwill Ambassador Slava Fetisov to draw attention to the issue of biodiversity, the importance of biodiversity and climate change, and that sort of regional visits, talking to governors, mayors local schools, civil society, about what we all can do together, I think, is really very important, and that's also something we are doing not just in Irkutsk but more generally we are seeking to talk to different groups about how everyone can make a contribution towards combating dangerous climatic change.

Q.: The UK's recent decision to increase its nuclear warhead stockpile by more than 40% could spur a global arms race. Would London be ready in the future to join an international arms control process? The U.S. wants to bring China to these talks, meanwhile Russia wants the UK and France to join this dialogue. What's London’s opinion on it?

A.: Firstly, I should say that I think there's been a misunderstanding. We have been very consistent that we keep our nuclear posture under constant review in the light of the international security environment. But what we seek to do is maintain a minimum credible independent deterrent, and this is more about the UK security and the security of our allies. It is designed to deter the most extreme threats to the security of the UK and our allies. But what our aim is to preserve peace, prevent coercion and deter aggression. None of that has changed. I think we have the smallest nuclear stockpile than any of the five recognized nuclear weapons states. So, none of that has changed, but what has changed is our assessment of what the minimum requirement for a credible deterrent represents. The previous ceiling was 225 warheads. We had intended to reduce that to 180 by mid-2020s, but we've looked at the changing security environment and including developments in technology and doctrine, including what other states are doing both the five recognized states but also others, and we've come to the view that in order to maintain a minimum credible independent deterrent we need to raise the ceiling by about 15% to 260. This is a ceiling, this is not a target, and it may not represent our actual stockpile. I'm afraid what is this is the recognition that the security situation has worsened. Again, this is not just about what is happening in Russia, were looking at a world where the DPRK has developed a nuclear weapons program, we are very concerned about the Iranian action that could result in the development of a nuclear-weapon-grade material, and we are seeing developments elsewhere, too. Against this factor, we have an obligation to make sure that our nuclear deterrent remains credible and effective against the full range of state nuclear threats. And this is what has led to this decision. It's not a change, if you like, in our overall policies, but responding to external changes.

In terms of arms control, we remain committed to the NPT. The change in our overall stockpile ceiling doesn't alter our minimum deterrence posture. It is fully compliant with our commitments under NPT. We've long been a champion of security benefits that the arms control can provide. We welcome the decision by Russia and the U.S. to extend the New START.

In terms of whether we should participate, we've heard public statements from Russia about the UK being included in the future multilateral arms control discussions. If there is a proposal on the table we will of course look at that. We have already taken substantial steps towards nuclear disarmament. We are maintaining a minimum credible nuclear deterrence, and we are very transparent about our overall approach in our doctrine. We would study a proposal, of course we would. We would study it, when we receive it.

Q.: The U.S. has withdrawn from the Treaty on Open Skies. Russia has made some efforts to preserve it, but Moscow has already said it isn't going to wait for long. How do you see the future of this Treaty, if it has any future? And considering the fact that UK and U.S. have allied relations, will London continue to exchange information with Washington on that subject anyway?

A.: We remain committed to the Open Skies Treaty, we think it helps build understanding and confidence between countries through military transparency. We think it is an important part of the global architecture that by improving transparency and mutual understanding by removing space for misunderstanding. We support it. We want it to continue. We think it makes a valuable contribution to European security for everyone. Of course, we've been disappointed when Russia decided to begin procedures to withdraw, particularly following Russia's continued non-compliance. We hope that Russia will reconsider its decision, return to full compliance of the treaty and work with all signatories to make sure that the treaty's obligations are fully complied with.

We are and will remain compliant with the obligations under the Open Skies Treaty. To our knowledge there have not been instances of data sharing with unauthorized parties and I think we've been very clear with the Russian government that we have no intention to share imagery and data with the U.S. or any unauthorized party in a way that would be inconsistent with our obligations. We think it's very important that all of us comply fully with the provisions. We want the treaty to continue. We would like Russia to review its decision and stay within the treaty.

Q.: As for the policy of sanctions and specific sanctions against Russia, are you planning to coordinate them with the U.S. and the EU, or does the UK have some special way now?

A.: We have our own legislation now that governs our sanctions policy. This is global legislation, so it is not country specific, except if it is UN arrangements. But we have a global sanctions policy and legislation now, which is fully independent of the European Union and others. Of course, when we are looking at international action and the serious human rights abuses or other issues, we do coordinate with allies and partners, and these include the U.S. and the European Union. You've seen some examples of that certainly in 2020 and indeed this week with the case of the action against some Chinese officials linked to the treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjaing. But this doesn't necessarily mean we impose them at the same time or against the same people or entities. There are instances when we will do this, when we are doing this, but we also clearly have our own independent space to take actions, where we consider it justified and lawful. And we will continue to maintain that space, while also cooperating close with our allies and partners.

Q.: The EU has imposed sanctions against a number of top Russian officials and representatives of law enforcement over the Navalny case. At the same time, Brussels has not backed proposals to sanction big businessmen who are believed to have close ties to the Kremlin, as there isn't enough of a legal basis for that. Will Britain share the same approach?

A.: We are guided by our own policies. We act in full accordance with our legislation. And we never speculate on sanctions before announcing them. Obviously, I'm aware of the case you are talking about, but we will take our own decisions. And any decision that we take will always be well founded on our legislation.

Q.: The UK enacted the Criminal Finances Act in 2018, when the first unexplained wealth orders were issued in regard to Russian assets. Is there any data showing the amount of assets, real estate, and finances of Russian citizens that have been frozen to date?

A.: As with the sanctions issue, the Criminal Finances Act of 2018 is not the one that targets Russia specifically, or any country specifically. They target economic criminals regardless of their nationality. I think that is a very important point to stress. This is about the UK, this is about us wanting to have strong anti-corruption legislation, it's about us seeking to have the highest standards that we can.

What we don't do and don't have separate statistics for how this might affect Russian citizens, because what we are trying to do is to crack down on crime, money laundering, illicit finance more generally. We have the Criminal Finances Act introduced a number of instruments, so we've got Unexplained Wealth Orders, we've got Account Freezing Orders, which freezes assets and accounts pending investigation. 2,500 thousand account freezing orders have been issued since they came in. But this is in overall just to demonstrate that this is something active and used and it's an important area for our law enforcement agencies.

Q.: The number of advocates for cooperation with Russia in countering the pandemic is growing in the EU. What is the British position on this? What`s about the cooperation between two countries on it? And might the reported side effects of the AstraZeneca affect somehow negotiations and plans to combine it with Sputnik V?

A.: Firstly, on the AstraZeneca vaccination, and indeed the Pfizer one, our independent medicines and healthcare agency have found them to be safe, they reviewed reports about side effects, and they are confident that the vaccines are safe. The European Medicines Agency has also looked at reports and have again – because they had already – but again have concluded that it is a safe and effective vaccine. We think this is very clear. In the United Kingdom, the mass vaccination program has been very quick, it's very successfully. Over 28.6 million people have had their first dose, and the evidence we have there is a strong immunity response even after the first dose, it takes a couple of weeks to kick in. I think we have reached 4 million of doses a week now. We have vaccinated 55% of adult population. We have seen since January very sharp falls in hospitalizations and deaths, and obviously the infection rates. It is a part of that huge lockdown but a part of it is attributed to the vaccination program.

We are also one of the largest contributors to the COVAX scheme. We began the international scheme to distribute vaccines, and that is now rolling vaccines out to low-income countries. We provided 548 million pounds for that, that's about $750 million, and that should translate into 1.3 billion Covid-19 vaccine doses for 92 developing countries this year. But we're very clear that we have to vaccinate at home, but we also have to help ensure that these vaccines are accessible everywhere. It's a point of fundamental fairness, it is also a point about making sure that everybody is safe from this horrible disease.

On that the Gamaleya Research Institute and AstraZeneca. You know, AstraZeneca is a British-Swedish company. It's a private company, but I think we welcome the cooperation between AstraZeneca and the Gamaleya Research Institute. My understanding is that the trials are ongoing. It's something we welcome but this is not the British government. We created conditions for fantastic science and pharmaceuticals and so on, but obviously they are collaborating with the Oxford University but AstraZeneca is not a state company.

And on Sputnik V. We have absolutely nothing against Sputnik V. I think it is a positive thing that Russia has a very strong scientific base, that Russia has developed three vaccines. I know that Sputnik V has now, I think, applied to the European Medicines Agency for a rolling review, and that has started. I saw that they have applied to COVAX, I haven't seen formal confirmation. I think that's clearly very positive because Russia needs vaccines, the world needs vaccines. We are supportive of safe and effective accessible vaccines.

Q.: Does Britain plan to take part in the St. Petersburg Economic Forum this year and on which level? Can we expect any British-Russian contacts and visits at a high or even highest level in 2021 or is it better to forget about this for now?

A.: On SPIEF. I'm hoping to attend SPIEF. Clearly, we are not at a stage yet where it is possible to know what the state of the pandemic will be like in early June. Whether people will come from the UK, private businesses and so on, I don't know. Many this year will remain cautious about travel. We will have to keep this under review. Similarly, in terms of senior visits and so on, I mentioned that we had Minister Morton came last year. We had a virtual visit of Carole Mundell this week. Quite how things will develop a year ahead, I think it is quite difficult to speculate. We are clearly hoping to receive a strong Russian delegation in Glasgow in November for COP26.

Q.: But do you have any confirmation for now who will represent Russia?

A.: The official invitations haven’t gone out yet, but of course Russia will be invited

Q.: Despite difficulties in the political sphere, what is London's attitude toward economic cooperation with Russia? How important is this aspect of bilateral relations? What are your preliminary expectations for bilateral trade in 2021?

A.: We support sanctions compliant trade and investment. I have a team here that works with British and Russian companies in order to encourage trade and investment and who work obviously with the Russian trade delegation in the UK. We don't have the final figures for 2020, but we know that - or at least according to our figures for the year that ended Q3 2020 - that Russia was our 26th largest export market, that was 4.9 billion pounds, roughly 5 billion. That was a reduction clearly primarily due to the pandemic, so we had been seeing growth up until then. But it was a reduction of around 6% which actually is probably not bad given the awful year for the global economy.

Russian exports to the UK during the same period almost doubled that. So, I think economic cooperation is remaining important. And I'm pleased to meet recently the minister of industry and trade, Denis Manturov, to talk about trade and economic relations. Trade contributes to low carbon agenda whether it is renewable energy sources, green finance, etc. We are also looking at services sectors and whether we can increase trade in services sector. And of course there is strong investment in both ways between the UK and Russia.